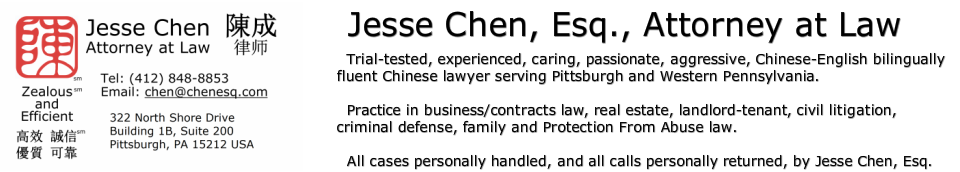

HOA to residents: You cannot park your truck in your driveway because it is not a "private, passenger-type, pleasure automobiles". Photo courtesy syracuse.com.

HOA to residents: You cannot park your truck in your driveway because it is not a "private, passenger-type, pleasure automobiles". Photo courtesy syracuse.com. The concept of the HOA grew the most in popularity following the growth of suburbanization the 1950s and 1960s. Since then, many suburban subdivisions are now either directly controlled by HOA employees (such as through a property manager), or contract with a management company. The HOA and its rules control the lives of all residents, and the HOA can overreach to such an extent that borders on the absurd.

Life in an HOA community can and do become micromanaged to a very great extent. If uniformity, conformity, and convenience are the most important values of a resident’s life, then living in a community with an HOA can bring many benefits. Property values in the entire community tend to be lockstep, and property owners can expect a certain level of maintenance performed to combat the lack of diligence by any one homeowner. Community amenities, such as recreational halls and pools, can improve the quality of life for residents.

The risk to micromanagement is that while great power requires great responsibility, HOAs can and do abuse power without any of its board members taking a shred of responsibility. HOAs are generally private entities run by board members. I shudder to think about the type of personalities who can be attracted towards contributing the amount of time and energy it takes to micromanage by serving on an HOA board. There are most certainly many civic-minded residents who take pride in maintaining a good community, but I also have dealt with many people with serious control issues who feel that being a petty despot as an HOA board member is their life’s calling. If folks of the latter type control a board, even the most inconsequential issues can become a nightmare. Do not just take my word for it; read for yourself real-life examples of HOA overreach:

http://gawker.com/5830257/the-horror-of-homeowners-associations

http://consumerist.com/2012/03/30/homeowners-association-remove-our-name-from-facebook-group-or-well-sue/

http://consumerist.com/2012/04/09/condo-owners-not-giving-up-fight-against-providing-dog-dna/

http://www.syracuse.com/news/index.ssf/2015/01/lawsuit_pickup_truck_not_welcome_in_fayetteville_development.html

What comes next? He doesn't know. "Should I go out and rob a bank? Then I'd be back here," he said. "But then I'd get out on bail." Photo of Mr. Prudente courtesy Tampa Bay Times.

What comes next? He doesn't know. "Should I go out and rob a bank? Then I'd be back here," he said. "But then I'd get out on bail." Photo of Mr. Prudente courtesy Tampa Bay Times. If the HOA abuses its power, what recourse does a resident have? The resident can complain to the HOA, which is asking the HOA to be self-policing. Governments in the United States have separation of powers (the executive branch, the legislature, and the judiciary) for a reason – so that if any one branch abuses its power, the others can take action. In contrast, HOAs are not governments. They are also judge, jury and executioner all in one, and if an HOA abuses its power without accountability, the only thing left for a resident to do (besides acquiesce to the abuse) is to sue. Also, because HOAs are not governments, their rules and agreements can be written up to the benefit of an HOA without the traditional issues that a governmental law is bound by – if a law is written poorly, such as in our above-mentioned “nuisance” definition, there are many mechanisms which are in place to protect an aggrieved citizen against a badly-written law. But if an HOA rule is written with breathtaking broadness, again, as above, a resident probably should not expect the HOA to take away its own power by narrowing the rule as written.

Moreover, once a lawsuit is brought, the aggrieved resident will face a discrepancy in litigation power – the HOA’s board members are almost always not personally threatened or liable even if the HOA loses its case, and the worst that can generally happen is that they lose their spot on the board. If a homeowner loses, the homeowner can face thousands of dollars in HOA fees, fines, interest, home foreclosure, jail time (http://www.tampabay.com/news/humaninterest/brown-lawn-means-jail-time/847365), and might even have to pay the HOA’s attorney.

Also, any additional assessment that comes from having to pay additional attorney’s fees to prosecute an action can be distributed across all residents’ assessments. For example, assume that a resident of a 200-unit community has been abused and the HOA is set on continuing its abuse. If both sides each spend $20,000 to fully litigate a case, then the abused resident has to pay $30,000 first to his or her lawyer. The HOA, if unable to pay its lawyer, can demand a special assessment (a special “lawyer tax”) of $30,000, spread across 500 residents, so that each resident (including our abused resident) only has to pay $60 extra, and spread possibly further over the course of a year ($5 a month extra), which would make the impact almost unfelt against any single resident and the HOA, while the costs might force the abused resident to simply give up.

From the perspective of HOA board members, then, there is virtually no personal risk to carrying out an agenda to either further an unhealthy desire for control and micromanagement, or even a specific desire to harm a neighbor. Even if a board member might be personally sympathetic, the desire for board members to vindicate their authority often trumps humane behavior. As one HOA board member, who I suspect did not shed a single tear for the poor resident stated:

"It's a sad situation," said board president Bob Ryan, who added that the association had followed all the correct procedures. "But in the end, I have to say he brought it upon himself."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed